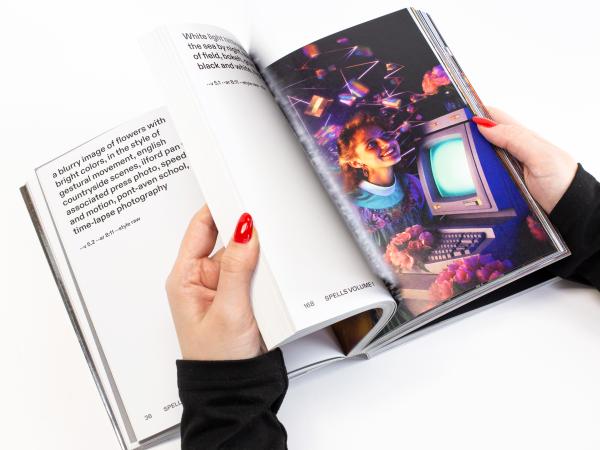

Five Creative Leaders Share Their Favourite Tactile Experiences

From photography to graphic design, we asked five industry-leading creatives to explore the enduring importance of analogue

The sensation of pulling a vinyl record from its sleeve and playing it for the first time, the wonder on children’s faces as they discover pop-up books and the thrill of a competitive board game... Here, five creative leaders recall their most treasured analogue experiences

Interviews by Douglas Heaven

Photographs by Perry Ogden

Perry Ogden is a British fashion and documentary photographer and film director, based in Dublin

I love magazines; I love seeing something printed on the page. For me, that’s a great end point for a photograph. You get incredible luminosity on screens, which can make an image look brilliant. But some images that look great on screen can look dead when printed.

Still, I work with everything. Phones take great photos, but the images are different. Digital is good for things such as modern architecture, where you have lots of concrete and glass. But when you have texture – interiors, clothing, bodies – digital doesn’t even come close to film.

I can usually tell if something has been shot on digital or film. I never feel the depth with digital; it flattens everything out. You have to work hard in post-production to create that depth. For example, pictures that I took in the late 1990s and early 2000s for Italian Vogue (pictured) wouldn’t work so well if they had been shot on digital.

When I work with digital, I’m always fighting it. It’s too sharp, there’s too much detail. When I was working on film all the time, I never looked for ways to make the image sharper. When digital came along, there was more of a groan than a celebration.

Vinyl by David Hepworth

David Hepworth is a music journalist, writer and publishing industry analyst. He edited Smash Hits in the 1980s and launched Q, Mojo and Empire. His book A Fabulous Creation: How the LP Saved Our Lives (Transworld) is out now.

Growing up, the only thing I ever wanted was long-player records – not just the vinyl but the whole LP. I used to fantasise about being locked in a record shop overnight. How wonderful would that feel? To me, it was like Disneyland. The combination of a vinyl record and its large paper and cardboard sleeve makes you feel an emotional attachment to music that you don’t get with any other medium.

As a 16 or 17-year-old, I’d go into town a couple of times a week and look through the new-releases rack, and I’d read the records – not hear them. You’d look at the track list, the liner notes. You’d take note of who the producer was, which record label put it out. You handled it before you owned it.

A record and its paper sleeve make you feel an emotional attachment to music

When you took it home, you then played it on a player that stayed in a corner of your room. You sat there and you concentrated on it. With a record, you’re aware of the mechanical process taking place as it spins around, which is very appealing.

Because you’re physically engaged with the music, you’re emotionally engaged, too. And when you put a record on, you left it on, because changing tracks before CDs was a delicate business. If you bought a record, you were going to invest a huge amount of time in it.

One of my favourite LPs was the self-titled second album by The Band. The cover is a photo of the group taken in the rain on a road near Woodstock. They look like a perfect band. They’re like soldiers in old photographs from the American Civil War, figures from some lost rural America. The designer chose to make the background brown, giving it earthy tones. When you listen to the record, the image grounds the music. The packaging and what’s inside are in perfect sync, and I never get fed up with looking at it 50 years later.

Graphic design by Geoff Waring

Geoff Waring is a graphic designer and photographer. He has also written and illustrated several award-winning children’s books

I’ve just finished designing a new font, Mental Block. Once it’s digitised, everyone can buy it. When I’m working on a design, I use the publishing software InDesign, but I’m rooted in print.

I’m in my fifties so I’ve lived through the shift to digital. People think of it as a total game-changer, but we’re still the same as we were when we lived in caves: we still eat, breathe and procreate, and we still want to look at pictures, whether they appear on a printed page or a website. But I’m passionate about print because paper exists in a way that digital files do not.

When you make a print product – whether that’s a book, magazine, poster or flyer – you get something tangible. That’s not true with computers. You can’t even open a file you’ve been emailed if you don’t have the right software. And what about Zip drives, Jaz drives and floppy disks – all these ways of storing data – that five years later nobody could open?

Yet the first books ever printed are still as legible today as they were 500 years ago. And if you go to a zoo, a museum or an art gallery, you can take away a little printed booklet that will remind you of that trip forever.

Because it’s a tactile object, you have an emotional response. Digital makes the need for printed things even more important.

The internet is great for a lot of things, but not for those that work best in print. As a creative designer, you really like to see things printed, whether you put them on your wall or stick them in a magazine rack.

The beauty of the web is that it lets you reach huge numbers of people very quickly. I’m going to set up an online shop but use it to sell prints of my new font, just as Caxton or Gutenberg or Dürer did. In that sense, nothing has really changed.

Books by Karen McCombie

Karen McCombie is the best- selling author of more than 90 children’s books, which have been translated into many languages. Her latest novel, Little Bird Flies (Nosy Crow), has been critically acclaimed and chosen as The Sunday Times Children’s Book of the Week

When I was young, we had 12 books in the house – four each for my parents and myself. We changed them weekly on a Saturday morning pilgrimage to the grey, Victorian wonderland that was the nearby Aberdeen Central Library.

I loved getting lost in the children’s section, dragging my fingers along the multicoloured spines, pulling the books out at random. At Christmas and on birthdays I’d receive a book token, and little by little, I began to build my own small library. Those titles now live on a dedicated shelf in my office. More than a doll or a teddy, they are signifiers of my childhood, and links to the quiet comfort and company of my parents.

Aspects of your childhood shape the adult you become. In spite of life’s glitches and difficulties, I’m as good as I can be thanks to two books that I met when I was 10 and 14 respectively: Little House on the Prairie and The Catcher in the Rye.

I loved getting lost in the library, pulling the books out at random

I write for older children myself, but when I read to younger ones, I turn to the fail-safe pop-up picture book There Are Cats in This Book by Viviane Schwarz. The children’s anticipation, excitement and bemusement as the silliness unfolds under flaps of card are a sheer delight.

Stick that story on a screen and it would be like watching your favourite band in concert as a tinny-sounding blur on your phone. Young children are relentlessly on the move, relentlessly curious, relentlessly hands-on. For them, the joy of a picture book is one-third story, one-third pictures and one-third moving parts. It was flat! But now it opens! Yay!

At the end of an author talk at a school, kids often rush towards me with a book in their hands to get a signed copy. But the less-confident readers are the ones I wait for. To see their own name written in a book, with an author’s signature underneath – it’s personal. It brings books alive for them. They’ll show their teacher and friends and their grown-ups at home. They can look at it again and again, and remember the day That Author came in and looked them in the eye and smiled and talked – and this might just be the book, the very book, that gets them reading others.

Board games by Graham Linehan

Graham Linehan is an award-winning comedy writer, best known for a string of successful sitcoms including Father Ted, Black Books and The IT Crowd

There are so many joyful elements to board games. A little overhead map of a place got me excited as a kid. Miniature worlds are thrilling; I find them almost spooky and that gets my pulse racing. It’s also to do with touch – opening the box and holding the dice in your hands.

My kids play games online – as do I, sometimes – but it’s more enjoyable to face someone across a table. I’m a big poker fan, and there are things your opponent does that tell you what you should be doing with your chips – you’re not able to see that online. Just a flicker of an eye and you know you’ve got them; it’s lovely. I shouldn’t take this much pleasure out of beating my 12-year-old, but I do.

I love dice games more than anything else; there’s something about dice that I find very attractive. A brilliant game that I think should replace Monopoly in every home is Lords of Vegas, which is about building casinos in Las Vegas. It’s one of those games where it’s fun to be extremely greedy. Everyone earns money on each turn, so there’s just this brilliant feeling of constant reward. It’s sneaky as well because you’re looking to take over the other players’ casinos. Another great game is King of New York, about being a King Kong-type monster attacking a city. The pieces are great and the dice are gorgeous.

All of this creates a kind of magic that exists in the air between you and the other players. I would never have seen it coming, but of course board games are going through a renaissance. It’s obvious that this would be one of the responses to an online world. You want a way of interacting with objects and people in front of you.

Our senses, including touch, are not fully used in a computer game. One reason I could never be a professional poker player is that my hands shake whether I have good cards or not; it’s the adrenaline. These things add up to an experience that disappears online.