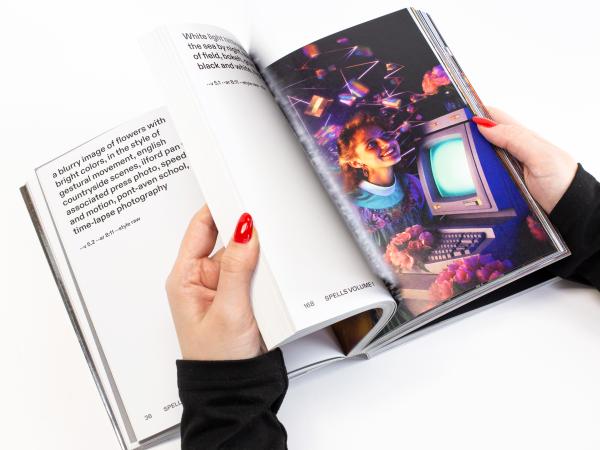

Laptop vs. Longhand: Is Reading on Paper better than Screen?

Studies show that reading something in print instead of on a screen helps us to retain the information more comprehensively. Michael Grothaus explores the phenomenon

It is not an understatement to say that digital mediums have taken over every aspect of our lives. We check what our friends are doing on the glowing screens in our hands, read books on dedicated e-readers, and communicate with customers and clients primarily via email.

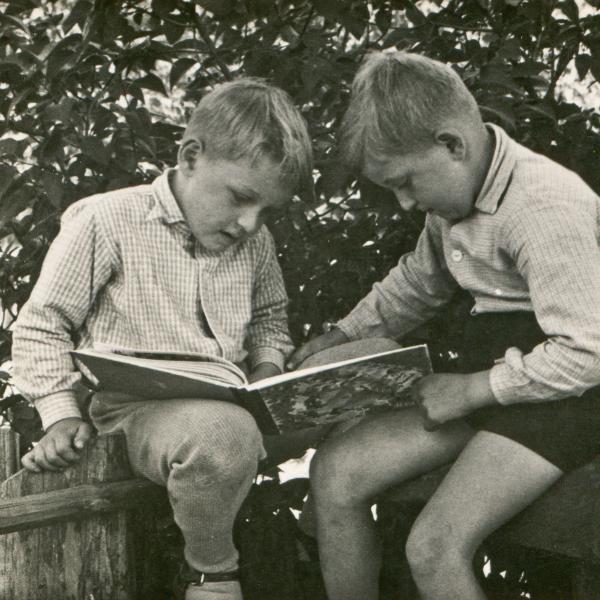

Yet for all the benefits the digital world has brought us, there is growing evidence that the brain prefers analogue mediums. Studies have shown that taking notes in longhand can help you remember important meeting points better than typing notes out on your laptop or smartphone. The reason could be that ‘writing stimulates an area of the brain called the RAS (reticular activating system), which filters and brings clearly to the fore the information we’re focusing on,’ according to Maud Purcell, a psychotherapist.

If that is the case, and the analogue pen really is mightier than the phone, it’s no wonder some of my colleagues have ditched their smartphones for paper planners.

Taking notes in longhand can help you remember important meeting points better than typing them out, while absorbing information from analogue mediums now appears to improve memory retention

While this has yet to be exhaustively investigated and understood, Dr Mangen, who now chairs E-READ, a European research network of interdisciplinary scholars and scientists researching the effects of digitisation on reading, says one explanation for the benefit of reading printed books may come down to what’s called meta-comprehension deficit.

‘Meta comprehension refers to how well we are “in touch with” our own comprehension while reading,’ says Dr Mangen. ‘For instance, how much time do you spend reading a text in order to understand it well enough to solve a task afterwards?’

One study revealed that people think they are better at comprehending information when they read it on a digital screen. This resulted in participants who read a text on screen doing so much faster than those who read it in paper format. Despite spending less time reading the material, the digital readers predicted they would perform better on a quiz about the text than those who read it on paper. Yet when the digital and paper groups were tested, the paper groups outperformed the digital groups on memory recall and comprehension of the text.

Should you print your emails?

Books are one thing, but do our brains absorb information better if we read from other physical mediums, such as newspapers and magazines? Not necessarily.

‘Length seems to be a central issue, and closely related to length are a number of other dimensions of a text – for example, structure and layout. Is the content presented in such a way that it is required that you keep in mind several occurrences/text places at the same time?’ asks Dr Mangen. In other words, she says, complexity and information density may play a role in the importance of the medium providing the text.

It may be that for certain types of text or literary genres (for example, romantic page-turners), medium does not matter much, whereas for other genres (cognitively and emotionally complex novels, for instance), medium may make a difference to comprehension or to the reading experience. But this remains to be tested empirically.

In other words, unless people are sending you novel-length emails (which, let’s face it, they shouldn’t be), you don’t need to rush to the print button, as reading short snippets of information on a screen probably doesn’t hinder memory retention or comprehension.

A place for print and digital

Dr Mangen also stresses that it isn’t correct to proclaim that information gleaned from print is always going to be just as good, if not better, for memory and comprehension than that learned from digital.

‘It is not – and should not be – a question of either/or, but of using the most appropriate medium in a given situation, and for a given material/content and purpose of reading,’ she says. She notes that ‘all media and technologies – old as well as new – have distinct user interfaces, and that the user interface of paper in some circumstances and for some purposes may support key aspects of reading (retention of complex information) or of study (writing notes in the margins) better than digital devices do.’

Slowly does it

If you’re a fan of digital books, then you’re not out of luck. Like the digital readers mentioned in the study above, you may think you are absorbing the information better than you actually are, and thus move through the book faster. A simple solution to this is to slow down and take more time reading the material, and you might absorb the information just as well as those who naturally take longer to read a paper book.

Michael Grothaus is a novelist and journalist.

References

Ackerman R and M Goldsmith (2011), “Metacognitive regulation of text learning:

on screen versus on paper”, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 17 March (1), 18-32.

Mueller PA and DM Oppenheimer (2014), “The pen is mightier than the keyboard: advantages of longhand over laptop note taking”, Psychological Science, 25 (6), 1159-1168.